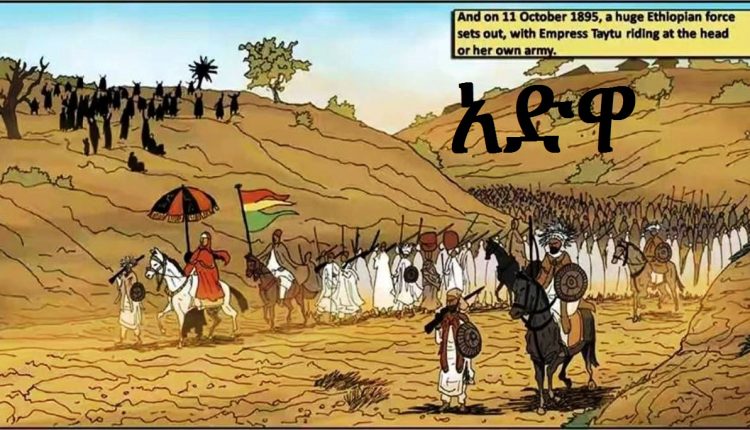

Adwa; Musolini vs Minilik II

Minilik of Ethiopia

The newly created Kingdom of Italy was a newcomer to the sharing of Africa, and as a late conqueror it had barely reached the last slice of the cake: Eritrea and Somalia, in the east of the continent on the so-called “Golden Horn”. On its western border lay the Kingdom of Ethiopia, then under the rule of King Negus Menelik. Cautious, Menelik knew that Italy was a dangerous enemy and that if he erred in his actions he would see his kingdom fall to the invaders as had happened elsewhere on the continent.

But Menelik was smart. At a time when neighbouring kingdoms were falling, he began to analyse the role of powerful European firearms and their ability to destroy any traditional army and undertook a series of missions and purchases with a view to modernising his army. When the time came for battle he planned to use his brand new rifles with the aim of avoiding the fate of initially successful armies that later collapsed (such as that of the Zulus).

For now, however, he was cautious. In 1889 he handed over the provinces of Bogos, Hamasien, Akkele Guzay and Serae to the Italians in exchange for the signing of a treaty guaranteeing their independence. Italy, however, expected more than that.

Italy

The Italians had made a little trick in the treaty. In the Amharic (Ethiopian language) version it clearly stated that the Ethiopian king could use the services of Italian diplomacy if he required them; however, the Italians had a version which stated that any relations must necessarily go through them. In other words, they had effectively turned Ethiopia into a protectorate with no right to make relations with other European powers.

Menelik was understandably unhappy about this. He was willing to negotiate with the Italians, but the whole point was to maintain his independence. Ethiopia should not, could not, be subject to a foreign power. And so, in the land of the legendary Prester John, the trumpets of war sounded.

The Italian march

Italy decided to subdue Ethiopia by force and sent General Oreste Baratieri, who subdued a number of insurgent towns and marched deep into Ethiopian territory. In 1895 a famine hit the region and both armies were affected; Baratieri knew that Menelik was weakened, but he himself had barely five days’ supply and decided to organise a retreat. He thought, perhaps rightly, that they could wait near the coast for the famine to ravage Menelik’s troops and restart the mission the following year (they had the possibility of supplying themselves by sea). But both his men and the Italian high command considered withdrawal unacceptable and insisted on the destruction of Menelik’s army, fearing that a year would give him time to better organise resistance.

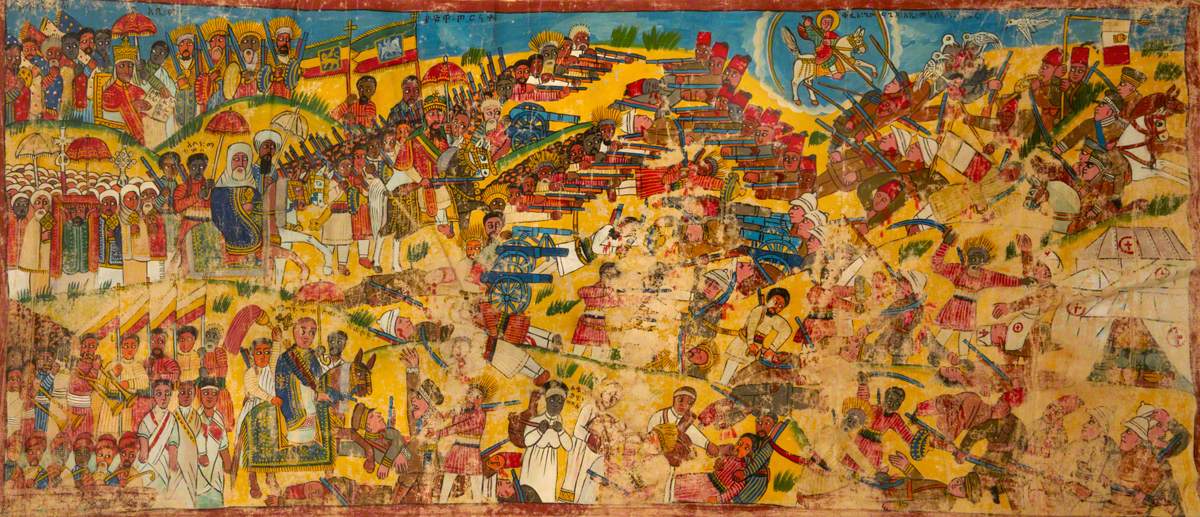

Baratieri ordered his soldiers to march on 29 February of that year to meet Menelik’s troops. The Ethiopians outnumbered them 5 or 6 to 1: Baratieri had almost 18,000 soldiers, Menelik had between 80 and 100,000 (the exact figure is not clear), but the Italians were not worried about this, as many wars in Africa had been fought in this way and had invariably ended in victory for the Europeans. They thought they would simply repeat history once again.

But Menelik was prepared. He divided his army into several sections and saved his elite troops, the Shewa, for a final counter-attack. In all, he had some 60-70,000 men armed with rifles (25,000 of whom made up his Shewa) and almost 20,000 armed with spears. He also had more than 10,000 mounted men. The battle was about to begin.

Preparations

We ended the previous episode with the march of the Italian commander Oreste Baratieri, who had launched his army of almost 20,000 men through the mountains of Ethiopia to subdue Emperor Menelik II, the last autonomous ruler of the African continent.

The situation was critical for both armies. Ethiopia was in a drought and food was hard to come by, and Menelik knew he did not have much time. But the Italian situation was no better and at the time of the conflict they barely had enough food for four more days.

As mentioned in the previous article, Baratieri was convinced that the best course of action was a retreat, but his second-in-command assured him that this would not be accepted by the Italian high command. The General also knew that he would soon be replaced, so he was keen to have the honour of being the first to give Italy a colony in Africa. His urgency would be his undoing.

Menelik II, for his part, needed a dramatic defeat of the Italians in order to end his colonial pretensions, and he knew he had little time. However, he knew the terrain and was careful: his plans were to lure the Italians into unfavourable terrain and force a fight. Fortunately for the Emperor, this would not be unnecessary. Italian irresponsibility would put them right where he wanted them.

The Battle

The Italians’ maps were old and not very accurate, and their troops were not as well equipped (they had new rifles, but used older versions in order to finish the cartridges and not lose them). On the night of 29 February 1895, the Italian troops split into 3 columns and began the march, but ended up moving several kilometres away from each other because the maps were less accurate than thought. This would prove fatal.

Matteo Albertone’s column turned at some point during the night to rejoin the rest of the army and unknowingly began to approach the position of Ras Alula, one of the Ethiopian army commanders.

Alula immediately sent emissaries to the Emperor to inform him that the Italians had left. The surprise effect had been broken and the Ethiopians had time to position their guns and men on the high ground surrounding the pass Albertone was heading for. There they had little to do but wait for the unsuspecting Italian troops.

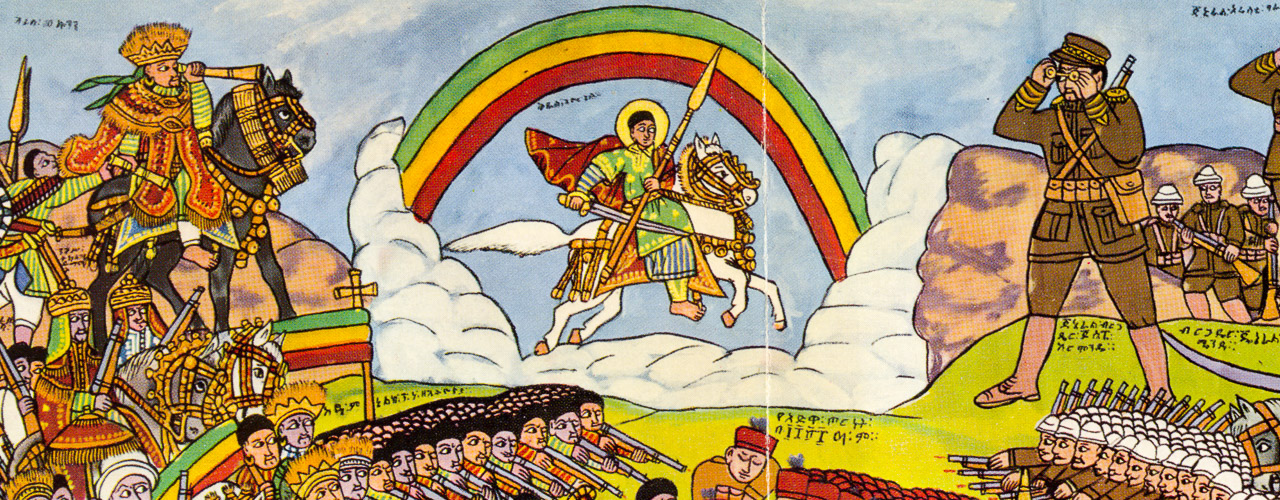

At 6am the battle began. Albertone soon saw his position ravaged by Ethiopian fire, including several guns that appear to have been donated by the Russians (who always had sympathies for the African emperor). As a side note, there are indications that Russian volunteer troops marched alongside the Ethiopians, but this has never been proven.

Their troops, Askaris from Eritrea, were at a great numerical disadvantage and despite their courage and efficiency soon began to lose ground. The army was disbanded when its commander, Albertone, fell prisoner to the Ethiopians, but by then the survivors were able to meet up with the troops of Giuseppe Arimondi, who had just arrived to support Albertone’s column. A sudden charge drove the Ethiopians back: it seemed that Italy still had a chance of winning.

The illusion did not last long. Arimondi was in a better position than Albertone, he had more men and a better knowledge of the terrain, but he was still outnumbered. He was able to resist with some ease the charge of Menelik’s less trained troops, but Menelik saw his chance and threw his Shewas at Arimondi’s position, forcing him to retreat quickly.

The last Italian column, led by Vittoro Dabormida, was never able to help his comrades. As it marched to Albertone’s aid it encountered strong Ethiopian positions and had to begin a slow retreat in search of a more defensible position. In doing so, however, he unwittingly ended up in a narrow valley where his troops were annihilated.

Consequences

The battle was over in less than six hours with a decisive Ethiopian victory. In total, Italy lost almost 11,000 men, with just under 6,500 killed, 1,500 wounded and 3,000 prisoners. Menelik II made the wise decision to avoid a campaign to expel the Italians from Eritrea and Somalia but instead used his advantage to force settlements according to Ethiopian perceptions and in doing so avoided a subsequent Italian campaign that could have been victorious.

In Italy, the defeat of Adwa precipitated an unprecedented crisis. In Ethiopia, it served to remind Africans that they could defend themselves. And in Europe, it reminded them that the continent was not completely subdued… yet.

Comment (0)